In Praise of Barney Lamm

I’m surprised there hasn’t been a song written about Barney Lamm. He lived such an extraordinary life of adventure, surrounded by legendary figures as he was creating his own.

He began building Ball Lake Lodge on the English River in Northwest Ontario in 1947, starting with a single two room log cabin on a beautiful sandy beach 50 miles north of the frontier town of Kenora. Over the next couple of decades he and his wife Marion built it into one of the most successful and famous fly-in fishing camps in all of Canada, the destination of rich and famous Americans as well as adventure seekers from around the world who enjoyed a bit of rustic comfort at the end of the day. Over the years Barney and Marion hosted John Wayne, the Getty Oil brothers, Natalie Wood, Patrick Hemingway, and James Hoffa, among others. Barney was an international sportsman of renown and he and Hemingway published a book about their safaris in Africa that Barney would give to favored guests.

He also built Ontario Central Airlines, perhaps the largest float plane airline in Canada during its heyday, and a great strategic business partner for his fishing camps—Ball Lake Lodge was his number one operation, but he also owned Maynard Lake Lodge, priced more for middle class guests.

Excuse me, but he would frown if I left it guests. He always insisted it was Guests.

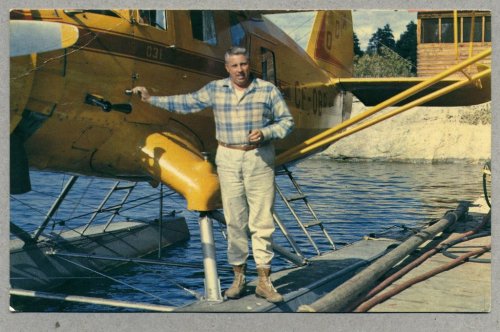

OCA had a fleet of Norsemen, the plane you see in the picture, a few Cessna’s, two Grumman Goose’s, a Beechcraft, and I recall the drama of a big PBY landing on its belly in the middle of Ball Lake a couple of times. I think he bought it as a curiosity but soon sold it.

He not only transported his guests to his camps, and the constant flow of supplies his camps needed, but he also transported passengers and supplies to the other camps on the English River’s chain of lakes, as well as the engineers and miners still exploring the wilderness for resources and knowledge.

He respected the Ojibway who worked for him and treated them fairly and was made an honorary chief of both the Grassy Narrows and White Dog Ojibway Reserves and later was Ontario’s Business Man of the Year.

When I worked for him I always found him to be a wonderful man, both demanding and generous, very clear about what he wanted, the best first boss a 15 year old kid could have. After a season spent in a ‘room and board’ apprenticeship were I earned my keep as a camp laborer, my second year I began to guide and Barney assured me that even if I was just 16 that I could guide two 50 year old highly successful businessmen out on the river and its lakes for four days of fishing, that I would ‘be in charge of my boat’, if I practiced servant leadership.

He didn’t use that label—it was a couple of years before Robert Greenleaf wrote his seminal essay on the concept where he coined ‘servant leadership’—but he helped me understand that as a fishing guide if I first and foremost saw it was my job to serve the men in my boat, to care for them, that when they saw they were the beneficiaries of that care, well then they would willingly grant me all the authority over them I needed to do my job, and that if I continued to use that authority to care for them, they would continue to grant me more and more.

I am delighted and proud to say it worked. I guided for three more years, for Barney in Canada and on the White River in Arkansas, and later I found bringing a servant leader leadership strategy to my start- up work was generative of the best outcomes. Thanks Barney.

Barney’s legend continued to grow when it was discovered that the English River was toxic, that it was polluted by a chemical plant 100 miles upstream. Though it would mean the destruction of his businesses, he blew the whistle on what was happening. When the Canadian government and industry tried to cover it up he flew in scientists to test the waters and it was discovered there was the greatest concentration of the highly toxic methyl mercury ever discovered. He and his family became the target of death threats when he demanded the problem be seen for what it was—an environmental disaster of the greatest magnitude that would have devastating impacts on the Ojibway for decades, for a century. And since that truth would lead to serious economic loss for many in the area he became the target of death threats; when next they were directed at his five daughters he sold their home in Kenora and moved away.

But he continued to fight until he died, certainly to protect his own economics self-interests, but always fighting for truth and justice for the Ojibway of Grassy Narrows and White Dog as well.

It’s a fight that continues, for neither have been accomplished.

Barney

February 18, 2015 at 7:07 pmI relived the summer of 68 when I read ‘To Guide – I Lied’! I became the ‘3rd guide’ that year too. Joe Loon 🙂 we all loved.